Alabama prisons—it’s getting harder and harder to get out alive.

Leola Harris is 71 years old, wheelchair-bound, suffering from end stage renal disease and

diabetes. She has served over 19 years of a 35-year sentence at Tutwiler prison. On January

10th, she was denied medical parole. The day of her hearing, the Parole Board granted parole

to just 1 of the 46 incarcerated individuals up for a hearing that day. Ms. Harris’s next parole

hearing will be in five years—if she survives that long.

As Leola Harris’s story demonstrates, it’s getting harder and harder to leave Alabama prisons alive.

Leola Harris, Sentence Date 11/24/2003

First, Alabama state officials have made it easier for the state to carry out death sentences. Death warrants no longer expire at midnight and appellate courts no longer review death penalty cases for plain errors. A “top-to-bottom” review of our death penalty protocols resulted in a swift return to business as usual. Meanwhile, the U.S. Supreme Court has made it more and more difficult for death sentences to be reversed.

Second, our prisons have become more deadly. The Department of Justice is suing Alabama because our prisons are so violent and dangerous that they violate the 8th Amendment’s prohibition on cruel and unusual punishment. The violence will only worsen if legislation to limit good time credits passes and understaffing continues. Last year 266 people died in Alabama’s prisons—95 were preventable deaths, the result of homicide, suicide, or drug-overdose. ADOC’s response to this crisis is to stop reporting monthly data on prison deaths.

Finally, it’s increasingly harder to get parole and leave prison alive. The 10% grant rate from 2022 was a new low, but the 2023 grant rate hovers near 3%. The numbers are just as dismal for medical parole and furlough grants. In 2020—the first year of the Covid-19 pandemic—only 5 people were granted medical parole. One of those five was my client, Justin Faircloth, who died of cancer within a year of his release. The most recent reports from ADOC show just 8 people in the medical furlough program.

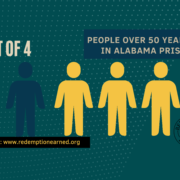

This is in a prison system where 1 in 4 prisoners is over 50 years old. We have thousands more elderly people in our prisons than we did a generation ago.

These are Alabamians like you and me, not just statistics. These are grandparents sitting in violent prisons. Dostoevsky said that “the degree of civilization in a society can be judged by entering its prisons.” Our prisons are brutal and filled with despair—what does this say about our state? The humanitarian crisis in Alabama’s prisons is a call to action. This legislative cycle is a chance to prove our state can be better. We need parole reform. There are people who have spent decades in prison are no longer dangerous. They and their loved ones have been punished enough. We need to offer them hope.

Please tell your legislators to support, House Bill 16.

Learn more about the bill HERE.

Professor Amy Kimpel, serves on Redemption Earned Inc.’s Board of Directors and as an Assistant Professor of Clinical Instruction at the University of Alabama School of Law in Tuscaloosa, Alabama.